FORSYTH COUNTY

Scroll down this page or click on specific site name to view features on the following Forsyth County attractions/points of interest:

Bethania, Historic Bethabara Park, Korner's Folly, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA), Old Salem, Reynolda House and Gardens, Winston Cup Museum

Fast facts about Forsyth County:

Created in 1849, the county was named for Colonel Benjamin Forsyth, an officer during the War of 1812.

The county seat is Winston-Salem. The town of Winston, founded in 1851 to be the county seat, was named for Major Joseph Winston, a Revolutionary War officer and a participant in the Battle of Guilford Courthouse; Salem, the Hebrew word for “peace,” was founded by Moravian settlers in 1766; the two bordering towns merged in 1913. Other Forsyth communities include Belews Creek, Bethabara, Bethania, Clemmons, Kernersville, Lewisville, Rural Hall, Tobaccoville, and Walkertown.

Forsyth County’s land area is 409.60 square miles. The population in the 2010 census was 350,670.

It is worth noting that the first official 4th of July celebration in the country took place in Salem in 1783; Krispy Kreme Doughnuts started in Winston-Salem.

Below: The Home Moravian Church and Salem College

Winston-Salem

Like Old Salem, two other Moravian settlements also afford visitors a glimpse of life in the backcountry in colonial North Carolina. Bethabara, described above, was the first to be founded. Bethania, meaning “a peaceful habitation,” was the second, founded in 1759, six years after Bethabara and six years before Salem. The restored area of Bethania is now recognized as a national landmark and the historic district is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. A small visitor center opened in April, 2007, in a portion of the restored Wolff-Moser House (circa 1780-1799). In addition to viewing the Wolff-Moser House, visitors can also see the 1895 Alpha Chapel, which now serves as the town’s meeting hall. A walking map guides visitors to more than two dozen buildings of historic significance, including Old Bethania School (1877), the Jacob Loesch House and Hauser-Reich-Butner House (both circa 1775), and the Bethania Moravian Church (1809). In 1849, Bethania was the western terminus of the 129-mile Fayetteville and Western Plank Road, the longest and costliest plank road in the entire South. From Winston-Salem, take Reynolda Road to Bethania Road and follow the signs to Historic Bethania. Turn left onto Horton Lane for the visitor center. Historic Bethania is open 10-4, Thursday-Saturday and other times by appointment. Nominal fee for guided tours, if available. 336-922-0434

Winston-Salem

Although Old Salem is by far the most publicized attraction, two other nearby Moravian settlements likewise reward visitors with an informative perspective on life in the backcountry in colonial North Carolina. The earlier of the two is Bethabara, founded November 17, 1753, making it the first Moravian settlement in North Carolina. Bethabara (meaning “house of passage”) is thus recognized as the birthplace of Winston-Salem and Forsyth County. Tours of the small community, which includes a blend of both original and replica buildings, begin at the modern visitor center, where a brief orientation film and several archaeological displays provide useful background to the site.

The 1788 Gemeinhaus is as much the focal point of the community today as it was 220 years ago. Interpreters in period attire take visitors through this unique structure, which is the only remaining 18th century German-American church with attached living quarters remaining in the United States. Guides provide information regarding social customs and various aspects of daily life. Visitors are free to explore other portions of Historic Bethabara at their leisure. Here they will find the Potter House (1782), which claims the distinction of being the oldest brick house in Forsyth County. Directly opposite the visitor center is the reconstructed palisade fort, the original of which offered the inhabitants of Bethabara a modest degree of protection from hostile natives during the French and Indian War. It is the only fort from this conflict in the entire Southeast standing on the site of the original.

Separating the palisade from the reconstructed community and medical gardens is a row of ex-cavated foundations. These stone cellars served as 18th century “refrigerators,” allowing families to store butchered meat and har-vested crops throughout the winter. At the rear of the gardens are several replica buildings representing the original 1754 village. State highway historical markers indicate that the famed “Great Wagon Road,” the all-important backcountry “highway” that stretched from Philadelphia to Georgia, passed by this very spot. From Winston-Salem, take US 52 North to Exit 115B. Turn right on University Parkway, then right again on Bethabara Park Blvd. Turn left on Bethabara Road. Parking for visitor center is on the left. Exhibit buildings at Bethabara Park are open 10:30-4:30 Tuesday-Friday and 1:30-4:30 Saturday and Sunday from April through November. Closed Thanksgiving Day. Nominal admission charged. 336-924-8191

Kernersville

The three-story brick house at 413 South Main Street in Kernersville has been called a “Victorian extravaganza,” “the strangest house in the world,” and “an amusement park with a front door.” Think Frank Lloyd Wright meets Frank N. Stein, and you start to get the picture. To folks in this quiet Forsyth County town, this architectural wonder is affectionately known as “Korner’s Folly,” a crazy-quilt jumble of twenty-two rooms built on seven distinct levels within a three-story house. Its narrow passages, low-ceilinged rooms, and gaudy furnishings and decorations bring to mind a carnival funhouse. Constructed over a two-year period from 1878 to 1880, its builder, Jule Gilmer Korner, originally envisioned the house as but a temporary residence. While the oddly designed house was still under construction, a dubious neighbor remarked, “This will surely be Jule Korner’s Folly.” The amused owner thought the description apt, and even went so far as to spell the name “Korner’s Folly” in mosaic tiles on the front porch.

An artist and interior designer by profession, Korner intended for his home to be a showplace of decorative ideas. Though most people would not recognize his name, Korner was responsible for creating the 19th century’s best-known product icon. As an agent for Blackwell Tobacco Company, Korner designed and painted the large Bull Durham ads on barns and businesses that helped make the Durham-based product the most recognized trademark in the world. Korner’s advertising murals were the precursor of today’s highway billboards. Following his marriage to Polly Alice Masten in 1886, Korner began to view the Folly as a permanent home. Thereafter, he saw the house as a work in progress, always changing, never to be completely finished even upon his death. The unusual nature of the house is apparent to visitors from the start. The first rooms guests enter, the foyer and dining hall, were not part of the living quarters when the house when first built. Rather, they enclose what had originally been a central carriageway that separated the house from the stables. These rooms also reveal decorative characteristics that run rampant throughout the house – recurring rope design work in doors, walls, and ceilings; mosaic tiles; massive fireplace mantels with decorative tiles; and delicate designs in raised plaster on walls and ceilings, often surrounding fanciful murals of cupids and cherubs. As visitors continue exploring the house, surprises await around every corner: narrow stairways, hidden passageways, and children’s playrooms with ceilings only six feet in height!

The largest room in the house is the reception hall, which runs the length of the second floor. Two enormous fireplaces on each end of the room are so designed as to provide “kissing corners,” private alcoves where young couples might spend a few moments unobserved. The entire third floor is occupied by a 75-seat theatre and stage. Nicknamed “Cupid’s Park” because of the subjects of the murals that decorate the walls, the theatre was the first private showplace in America, converted from a billiard room in 1897. The theatre is still in use today, with public performances held periodically throughout the year. After the death of her parents, Dore Korner opened the house for public tours in the 1930s. Thereafter, the “Folly” left the Korner family and was used over the years as an antique shop, funeral home, architect’s office, and apartment building.

The house endured a ten-year vacancy before local residents established a non-profit foundation for the purpose of preserving and refurbishing their town’s treasure. The Folly was reopened for tours on a limited basis in 1997. Modern heating and air conditioning was installed in 1999, followed next by landscaping improvements. Many other improvements have been made in the time since. Cracked plaster, tattered curtains, broken tiles, and any number of other items have been repaired or replaced, so that visitors seeing this ostentatious home today can better appreciate its finer points. From I-40 Business, take the Kernersville exit and head towards downtown. Korner’s Folly is on the right. Korner’s Folly is open for self-guided tours from 10:00-3:00 Thursday and Saturday, 1:00-5:00 Sunday. Admission charged. Viewing all rooms requires guests to pass through narrow doorways and traverse steep, narrow steps.

Winston-Salem

Visitors on a guided tour of Winston-Salem’s Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts [MESDA] will take a 90 minute “journey” that whisks them across seven southeastern states and 150 years! For nearly half a century, MESDA has been showcasing the nation’s finest collection of pre-1820 decorative art from Maryland, Virginia, North and South Carolina, Georgia, Kentucky, and Tennessee. MESDA’s extensive collection includes furniture, textiles, paintings, ceramics, and metal ware. A novel approach has been taken to enhance the way in which the items are displayed, placing them in settings in which their artistry can best be appreciated. Although the Museum includes six small galleries in which artifacts are showcased in a traditional manner, most items are presented in period rooms that have been painstakingly fashioned to recreate actual rooms from southern homes dating from 1690 to 1820. As visitors move from one room to the next, they find themselves traveling from Maryland’s Chesapeake region to the Virginia tidewater and all the way from the South Carolina low country to the North Carolina backcountry. The first room visitors enter, for example, recreates the living quarters of a home in New Kent County, Virginia, circa 1690, followed by an English cottage home built in Somerset County, Maryland at the turn of the 18th century. A parlor, bedroom, and hallway are copied from an Edenton, North Carolina estate circa 1760. Still another room reproduces the rustic McLean House, built in Guilford County circa 1766; the Museum’s reconstruction of the log house utilizes much timber from the original structure. The final room on the tour replicates a dining room from a South Carolina home circa 1820. Each decorative art on display has been documented as having been handcrafted prior to the advent of the industrial age. Examples of baroque, rococo, and neo-classical furniture abound. North Carolinians will take pride in the wonderful examples of Roanoke River Valley and Chowan River Valley styles of furniture.

Also housed in the Horton Center are the Old Salem Toy Museum and the Old Salem Children’s Museum. The latter is aimed at youngsters aged 4 to 9, providing hands-on activities to help stimulate learning. Children can play in a scaled down replica of Old Salem’s Miksch House, crawl through a maze tunnel, try on period costumes, and build with bricks, to cite but a few activities. The Toy Museum features an incredible assortment of toys – more than 1,200 items make it one of the best collections in the nation. Among the vintage playthings on display are extravagant doll houses crammed with intricate miniatures; circus acts and animals; an original Punch and Judy Theatre, circa 1830-40, complete with original puppets; parlor games (including a “magic lantern,” the inspiration for the motion pictures which were to follow); and, of course, toy trucks, trains, and boats – even a model of the Monitor! MESDA is located at the south end of Old Salem. Cross the pedestrian bridge from the Old Salem Visitor Center to get to the Frank L. Horton Museum Center at 924 South Main Street. MESDA is open 9-5 Monday-Saturday and 1-5 Sunday. A MESDA tour is included as part of the Old Salem “All-in One” ticket, or admission to MESDA can be purchased separately. 336-721-7300

Winston-Salem

A trip to Old Salem is a step back in time. While modern skyscrapers loom in the distance, visitors will quickly find themselves transported to a by-gone era and a different way of life. Salem had its origins in the mid-18th century, when Lord Granville sold a 98,985-acre tract of land in the North Carolina backcountry to Moravians living in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Count Zinzendorf of Austria had been a benefactor and protector of the Moravians in the Old World, and this land in the New World was given the name “der Wachau” – Anglicized as “Wachovia” – in honor of his ancestral estate. In 1753, the earliest Moravians to arrive in the Carolina frontier established a temporary settlement called Bethabara, Hebrew for “house of passage.” It was not until 1766 that the permanent village of Salem, Hebrew for “peace,” was established. Salem, along with other Moravian settlements in the area, flourished until the mid-19th century, when surrounding settlements gradually absorbed them. The town of Winston was established in 1849, and Winston and Salem merged in 1913. The original Moravian village had all but vanished when, in 1950, Old Salem, Inc. was established to preserve what remained and to initiate restoration efforts. Hard work and determination resulted in a recreated village that draws thousands of visitors annually.

A modern and expansive visitor center makes a good first impression and provides an introduction to Old Salem. Following this orientation, visitors cross a covered wooden bridge to begin their exploration of the old town. Much of the restored area is centered on Salem Square, and there are a dozen or so buildings open to the public. The restored area encompasses several blocks. The oldest building is the Single Brothers House, built in 1769. Moravian society called for individuals to be grouped with others based on age, sex, and marital status. Thus, male adolescents were moved to the Single Brothers House at an early age, and here they were expected to become proficient at one of the many guild trades. Within the Single Brothers House are both living quarters and workshops for tinsmiths, weavers, tailors, potters, joiners, coopers, and gunsmiths.

Other buildings open to the public include the Boys’ School (1794), which now houses the Wachovia Museum; the Miksch Tobacco Shop (1771), the first privately owned house in Salem; the Market-Fire House (originally built in 1803 and reconstructed in 1955), which served as both public meat market and fire station; the Samuel Vierling House (1802), home of Salem’s most renowned physician; the John Volger House (1819), the home and shop of Salem’s best known silversmith; and Salem Tavern, where President Washington was entertained during his 1791 tour of the southern states.

The Home Moravian Church remains an active house of worship, greeting visitors to Old Salem. Another historic church is St. Philips, which met the needs of the community’s black population. It was here that the Emancipation Proclamation was first read publicly in North Carolina. The alluring aroma of fresh baked breads, cakes, and cookies will make it obvious to visitors that the famous Winkler's Bakery (1800) is open for business. The merchant shop of Traugott Bagge (1775), now operated by Old Salem as a Museum Store, is likewise still meeting the needs of its customers.

The famous tin Coffee Pot which stands at the northern edge of town has become a symbol for Old Salem even though it has little real connection to the original village. Built by tinsmiths Samuel and Julius Mickey as an advertisement for their business, it originally stood in front of their shop at South Main and Belews Streets. The building was torn down when Interstate 40 was built, and the coffee pot, which measures 7’ 3” in height, was moved to its present location at that time. The Visitor Center is open 8:30-5:30 Tuesday through Saturday and 12:30-5:30 Sunday. Buildings are open 9:30-4:30 Tuesday through Saturday and 1:00-4:30 Sunday. Admission is charged and includes entrance not only to the various buildings in Old Salem, but also admission to the Museum for Early Southern Decorative Arts [MESDA], the Toy Museum, and the Children’s Museum. 336-721-7300.

Winston-Salem

A Winston-Salem landmark for nearly a century, Reynolda House offers a view into the life style of American high society prior to the Great Depression. It also serves as a showcase for true masterpieces of American art. Nearby gardens, estate buildings and village shops make for a full day of activity. The Reynolda House and estate just go to show that you never can tell where an office romance might lead. Back in 1903, tobacco magnate Richard Joshua Reynolds hired young Katharine Smith as his private secretary. Two years later, the 55-year-old bachelor married the attractive employee, 30 years his junior. Beginning as early as 1906, the couple began acquiring land for their dream home, and from 1912-17, their 1,067-acre estate was in various stages of development. The low roofline, recessed porches, squat columns, and shed dormers characterize their country house as a “bungalow,” but with 42 rooms it was, and remains, anything but average. The house was designed by noted Philadelphia architect Charles Barton Keen, who went on to design several other prominent buildings in North Carolina.

Visitors to the home today can take a self-guided tour through most areas of the house. The admission fee includes an orientation video, oral history kiosk, and an audio tour. The house has been carefully restored to its 1917 appearance, and the furnishings reflect the eclectic tastes of the owners. A two-story reception hall, surrounded by a cantilevered balcony, is at the heart of the house, with a dining room and library on either side, sun and tea porches to the front, and three separate porches overlooking a lake to the rear. The bungalow’s west wing includes a butler’s pantry and private kitchen, while the east wing includes the individual studies for both Richard and Katharine. One of the most remarkable features of the house is the Aeolian organ; although the organ itself is positioned in one corner of the reception hall, the pipes actually occupy portions of both the second floor and attic. Several attic rooms showcase vintage family clothing, while in the basement visitors will see the indoor swimming pool, squash court, game room, shooting gallery, and one-lane bowling alley installed in 1936 by Mary Reynolds Babcock, who inherited the property from her parents.

Since 1967, Reynolda House has served as a showplace for some of the best works of American art, from 1755 to the present. No effort has been spared to acquire pieces that are considered to be among the individual artist’s finest works. Featured portraitists include such notables as Gilbert Stuart, Charles Wilson Peale, Thomas Sully, and John Singleton Copley. Frederic Remington’s bronze statue “The Rattlesnake,” done in 1908, is on display. One of the smaller landscapes decorating the walls is “Witch Duck Creek,” a North Carolina scene done in 1835 by Joshua Shaw. Having enjoying all that Reynolda House has to offer on the inside, visitors can then relax in the adjacent Reynolda Gardens of Wake Forest University. Originally a part of the Reynolds’ estate, the Gardens were given to the University in 1958. Restored to the appearance of the original design, the gardens are divided into two distinct sections. Perennials and flowering shrubs, hundreds of rose bushes, and two decorative fountains are found in the Greenhouse Gardens. The less formal Fruit, Cut Flower, and Nicer Vegetable Garden features fences, pathways, arches, and shelters amid a variety of herbs and vegetables and more than 800 rose bushes. From University Parkway in Winston-Salem, turn onto Coliseum Drive, then onto Reynolda Road. Hours are 9:30-4:30 Tuesday-Saturday and 1:30-4:30 Sunday. Admission charged. 336-758-5150

Winston-Salem

Dale Earnhardt’s record-setting seven champion-ships, Richard Petty’s remarkable 200th victory, and the first checkered flags in NASCAR’s premier series for such drivers as Jeff Gordon, Tony Stewart, Jimmie Johnson, and Dale Earnhardt, Jr., all took place when the sport’s primary sponsor was the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. From 1971 through 2003, the most talented stock car drivers in the world competed for the Winston Cup, and it was during this period that NASCAR skyrocketed to national popularity. The Winston Cup Museum in Winston-Salem pays tribute to R. J. Reynolds’ 33-year sponsorship with a collection of race cars, show cars, trophies, driver uniforms, helmets, and other miscellany.

While specific cars and exhibits vary from time to time, the primary purpose of the Museum – to honor NASCAR’s Winston Cup era – remains a constant. One means of achieving this is through an impressive mural that wraps around three interior walls, a visual timeline that pictures many of the sport’s most popular drivers on and off the track, racing photos from venues around the nation, pre-race festivities and victory celebrations. A showcase at the end of the timeline features a trophy naming the champion driver for each year from 1949 to 2003, beginning with Red Byron, NASCAR’s inaugural champion, and ending with Matt Kenseth. Cars making up the museum’s “field” include show and competition cars driven by some of the sport’s most iconic figures, including Richard Petty, Darryl Waltrip, Jeff Gordon, Tony Stewart, Dale Earnhardt, Sr. and Dale Earnhardt, Jr.

In 1985, R. J. Reynold’s intro-duced “The Winston Million,” giving drivers the chance to win one million dollars by winning three of four “crown jewel” races: The Daytona 500, NASCAR’s most prestigious event; the Coca-Cola 600, the longest; the Winston 500 at Talladega, the fastest; and the Southern 500 at Darlington, the oldest. During the 15-year history of this event, only two drivers were able to claim the prize. Bill Elliott won the inaugural Winston Million, earning him the nickname “Million Dollar Bill.” Jeff Gordon won in 1997, the final year of the event, by taking the checkered flags at Daytona, Charlotte, and Darlington. The Winston Million was replaced by the Winston No Bull 5 as part of R. J. Reynolds’ tribute to NASCAR’s 50thanniversary in 1998. Also introduced in the mid-1980s was an all-star event. What is now known as the All-Star Challenge began as “The Winston,” an event open only to a select field of drivers. Held all but one year at the track in Charlotte, winners of “The Winston” include Darryl Waltrip, Davey Allison, Rusty Wallace, Jeff Gordon, Mark Martin, and both Dale Earnhardt, Sr. and Dale, Jr. The last driver to win the event in 2003 was an up-and-comer named Jimmie Johnson. To get to the Museum, take Exit 110B off US 52 in Winston-Salem. Turn west onto Martin Luther King Jr Drive and drive approximately ½ mile. Hours are 10-5 Tuesday-Saturday. Days and hours may vary during local race weeks. Admission charged. 336-724-4557

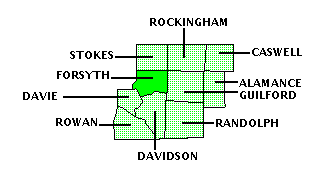

Forsyth County is bordered by DAVIDSON, DAVIE, GUILFORD, STOKES, and YADKIN (Region Eight) counties.

Return to REGION SIX HOME PAGE.

Return to GEOGRAPHIC REGIONS HOME PAGE.