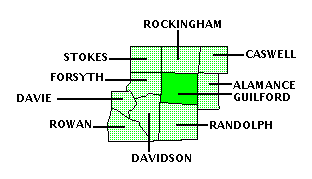

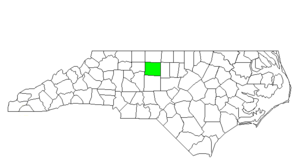

GUILFORD COUNTY

Scroll down this page or click on specific site name to view features on the following Guilford County attractions/points of interest:

Blandwood Mansion, Charlotte Hawkins Brown State Historic Site, Cline Observatory, Greensboro Historical Museum, Guilford Courthouse National Military Park, High Point Museum, International Civil Rights Center, Mendenhall Plantation, Natural Science Center of Greensboro, Tannenbaum Historical Park & Colonial Heritage Center

Fast facts about Guilford County:

Created in 1771, the county is named for Francis North, first Earl of Guilford, a British statesman.

The county seat is Greensboro, named for Nathanael Greene, a major general of the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War in command of American forces at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse. Other communities include High Point, Jamestown, Stokesdale, Summerfield, Whitsett, and parts of Archdale.

Guilford County’s land area is 649.42 square miles; the population in the 2010 census was 488,406.

It is worth noting that High Point earned a reputation as “Furniture Capital of the World.”

Below: Statue of General Nathaniel Greene at the Guilford Courthouse National Military Park in Greensboro

Greensboro

Once home to John Motley Morehead, one of North Carolina’s best known and most accomplished governors, Blandwood Mansion is also recognized as the prototype for the Italian Tuscan Villa style of architecture popularized in America during the mid-nineteenth century. John M. Morehead was a leading statesman and entrepreneur in the years leading up to the Civil War. A Chapel Hill graduate, Morehead initially embarked upon a legal career but soon found himself in the role of public servant, holding a position on UNC’s Board of Trustees for many years, serving in the North Carolina House of Commons, and filling two terms (1841-1845) as state governor. Morehead was the very embodiment of the term “progressive.” Described as a man of great vision, and sometimes referred to as the “father” of modern North Carolina, Governor Morehead advocated the establishment of common schools, a school for the deaf and blind, an insane asylum, and a penitentiary system. A proponent of education for women, he established Edgeworth Female Academy in Greensboro, in part as a means to educate his five daughters. Seeking to further North Carolina’s economic development, the Governor also promoted a statewide system of railroads. Following his second term in office, Morehead entered the business world, and from 1850 to 1855 he served as president of the North Carolina Railroad.

In 1844, Governor Morehead engaged famed architect Alexander Jackson Davis, designer of the state capitol building in Raleigh, to draft plans for a new addition to his private home in Greensboro, something that would befit Morehead’s political and social stature. The oldest portion of the house, built in the late 1700s, was a simple two-over-two frame structure. When newly-married John Morehead purchased the house from his wife’s step-father in 1825, he had an addition put on that doubled its size. Architect Davis saw in the second expansion of Morehead’s house an opportunity to introduce a new architectural style which was to become known as Italian Villa. The two-story addition included east and west parlors on opposite sides of a central hallway on the ground floor, and two bedrooms on either side of the hallway upstairs. Extending in the front center of the addition was a three-story tower. Matching dependencies to the left and right of the addition – one serving as a kitchen, the other as Morehead’s law office – were joined to the main house by decorative arcades. A sketch of the Blandwood estate in A. J. Downing’s Landscape Gardening and Rural Architecture, published in 1844, helped to popularize the Italian Villa style in America. The original watercolor of Davis’ plans for Blandwood is now a part of the collection of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Visitors will note that original gas lamps still continue to illuminate the grand entry outside the home. Inside, family portraits adorn the walls of most rooms, giving guests a sense of visiting a home still lived in by the Governor and his children. Personal effects are scattered throughout the house, including the very cradle in which John Morehead slept as an infant. In the replica of Morehead’s law office is a massive safe from the North Carolina Railroad. Its combination is unknown, so the safe remains unopened, still guarding whatever items were last placed within it for safekeeping. Guided tours are given 10-5 Tuesday-Saturday and 2-5 Sunday, with the last tour starting one hour before closing. Admission charged. 910-272-5003

Sedalia

In 1987, the State of North Carolina honored the late Dr. Charlotte Hawkins Brown for her lifelong efforts to bring quality education to black students in her native state by establishing a memorial in her name. Located at the historic Palmer Memorial Institute in Sedalia, the Brown Museum has the distinction of being the only state historic site honoring a woman, and the only one honoring a black American. The site seeks not only to honor Dr. Brown as an individual, but also to link this outstanding educator and the Palmer Memorial Institute over which she presided for 50 years with the larger themes of the educational and social history of African Americans in North Carolina.

Born in Henderson, NC, June 11 1883, Lottie Brown moved with her family to Cambridge, MA at the age of six. There, she attended Allston Grammar School, Cambridge English High School, and Salem State Normal School. While still enrolled at Salem State, the American Missionary Association offered the 18-year-old girl a teaching position in her native state. Dissatisfied with the lack of quality education available to blacks in the South, and wanting to make a difference, Hawkins accepted. She arrived in Sedalia in 1901 and taught one year at Bethany Institute. Although Bethany had been established in 1870 by the AMA to provide a vocational and liberal arts education to black students, the school closed one year after Hawkins’ arrival due to lack of funds. The young teacher had already made an impact, however, and the community encouraged Hawkins to remain in Sedalia and continue to teach. A successful fund-raising trip to New England enabled her to open a new school in a converted blacksmith’s shop in the fall of 1902. From such humble beginnings, the determined Charlotte Hawkins built Palmer Memorial Institute, named in honor of friend and benefactor Alice Freeman Palmer, into one of the nation’s most renowned schools for African American students.

Hawkins married Edward S. Brown in 1911, and for a time her husband taught at the school and helped with its administration. He later left PMI to take a teaching position in South Carolina, and although the couple eventually divorced, Mrs. Brown continued to use her married name for the rest of her life. Concerned that her students achieve socially as well as academically, Dr. Brown authored a book entitled The Correct Thing To Do, To Say, To Wear in 1941. The instructional book was required reading for all PMI pupils, and students adhered to a strict code of conduct. During her tenure as president, more than 1,000 students graduated from Palmer Institute. In later years, more than ninety percent of PMI students attended college, and nearly two-thirds of those sought post-graduate degrees.

A trip to the Memorial begins at the visitor center, presently located in the former Carrie Stone Teachers Cottage. Num-erous artifacts pertaining to student life at Palmer are displayed, and a short video on Dr. Brown’s career is shown on request. Efforts are underway to transform the former Charles W. Eliot boys’ dormitory into the new visitor center. A guided tour of the Canary Cottage – so called because of its bright yellow paint scheme – reveals a cozy environment, one which served as Dr. Brown’s home and office. Visitors are able to take a self-guided walk around the PMI campus. Although the Alice F. Palmer Building, the main building on campus, was destroyed by fire in 1971 – thus contributing to the school’s closing – several other structures remain, including Kimball Hall (cafeteria), Galen Stone Hall (girls’ dormitory), the bell tower, and the Tea House. Dr. Brown’s grave is also located on the property. Hours are 9-5 Tuesday through Saturday. Admission is free. 336-449-4896

Jamestown

Looking for something to do on a Friday night? The Cline Observatory on the campus of Guilford Technical Community College [GTCC] in Jamestown is small on the outside, but there’s an amazing amount of space – as in outer space – on the inside. Skies permitting, the Ob-servatory is open every Friday evening year round for free viewings of celestial bodies from every corner of the universe. J. Donald Cline con-tributed money to GTCC in the 1990s for the purpose of building an observatory where both students and the general public could see and learn about the universe. In recognition of Cline’s generous gift, the observatory, which opened in September 1997, was named in his honor. The telescope is housed in a circular, domed building. A slit in the roof opens during viewings, and the dome can be rotated so that objects in every direction of the sky can be seen. The telescope itself looks rather small, only about 40 inches in length; by comparison, the famous Hubble telescope which has been orbiting Earth since 1990 is the length of a bus! Repositioning the telescope, a process called “slewing,” is done by using a control pad that looks similar to the joy sticks used for video games. A computer screen displays a map of the current positions of planets, stars, and other heavenly bodies, so that the telescope can quickly hone in on specific objects.

The “stars” of the weekly viewings aren’t usually the stars at all, but rather our nearby neighbors – Earth’s sister planets and our very own moon. Since Earth’s orbiting satellite is (in celestial terms at least) a mere stone’s throw away, the Cline telescope is able to bring details of the lunar surface into sharp focus. Even senior citizens gasp like children when they gaze through the lens at the stark, ashen surface of the moon. Visitors to the observatory might get to see Venus, Mars, Saturn, or Jupiter, or perhaps a comet or meteor shower, depending upon where these bodies are located in the heavens on that particular night. When not viewing something within our own solar system, the telescope hones in on individual stars or globular clusters of stars from galaxies unimaginable distances away.

During daylight savings time, programs start one-half hour after dusk. During standard time, they start at 7 PM. The informal sessions last about two hours, depending upon the number of visitors, interest, and, of course, weather conditions. Visitors arriving early enough can take advantage of the “Sidewalk Solar System.” Each planet has a marker positioned along a path outside the observatory providing basic information about the planet. The marker is positioned in the relative distance from the observatory that the actual planet is from the sun. Markers for Mercury, Venus, and Earth are just outside the door; Saturn’s marker, by contrast, is about the length of a football field away; from Neptune’s marker, the domed roof of the observatory is all that can be seen; Pluto, recently stripped of its designation as a planet, is out of sight of the observatory altogether. Poor Pluto! From I-85, take Exit 118 (US 29/70) toward Jamestown. Exit onto Guilford College Road and turn right. Turn left on Vickery Chapel Road North and drive 1.3 miles. Turn right on High Point Road, drive .3 miles, and turn left on Rochelle Road. Turn right on Montgomery. The Observatory is visible on the right, overlooking the pond. Admission to the Cline Observatory is free. Programs are held only when weather conditions permit. Call 336-454-1126 extension 2620 for further details.

Greensboro

From 18th century log homes to a 20th century street scene, from First Lady Dolley Madison to first rate story teller O. Henry , and from a struggle for freedom waged with muskets to a fight for equality staged at a lunch counter, the Greensboro Historical Museum recalls the history of the city, county, and region. The largest artifact on display is the building itself -- the 1892 sanctuary of the First Presbyterian Church, listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Museum makes good use of its considerable exhibit space, and the facility sparkles with historic gems. One gallery focuses on Greensboro native William Sidney Porter, better known by his pen name O. Henry and the author of such delightful short stories as “The Ransom of Red Chief” and “The Gift of the Magi.” Another gallery honors Guilford County’s Dolley Madison, America’s First Lady during the War of 1812. Yet another exhibit spotlights “Jugtown pottery,” a name generally applied to earthenware from Seagrove, NC and the surrounding area. In 1917, Raleigh natives Jacques and Juliana Busbee helped popularize the region’s pottery by selling pieces crafted by J. H Owen and others in a tea shop in New York City’s Greenwich Village. In 1921, they established the “Jugtown Pottery” brand. A variety of earthenware from many Seagrove-area potters is displayed.

The Museum also features exhibits on the pivotal Revolutionary War battle of Guilford County Courthouse, fought March 15, 1781, and on an altogether different kind of struggle waged in February 1960, when, in a quest for equal rights, four black students from North Carolina A. & T. staged America’s first sit-in at the local Woolworth store. This building now houses the International Civil Rights Center and Museum.

The Italianate-style residence known as “Belle Meade,” built in 1867 for Henry and Eliza Tate, was a well known Guilford County home for nearly a century. The Museum acquired furniture and accessories from the home prior to its demolition in 1954, and three “Belle Meade” rooms – parlor, dining room, and bedroom – have been meticulously recreated. These rooms exhibit many Renaissance Revival and Rococo Revival furnishings and flourishes popular during the last half of the 19th century. By contrast, the Mendenhall-Simpson room displays more functional Piedmont area furniture from the early-to-mid 1800s.

The “Welcome to the Gate City” exhibit on the Museum’s third floor is truly a step back in time, recreating the look and feel of a Greensboro city street circa 1905. Guests can visit the Richardson & Farris Drug Store, where Will Porter worked as a registered pharmacist in 1881. Druggist Lunsford Richardson was aptly proud of the various remedies he concocted behind the counter, including Tar Heel Sarsaparilla and Yellow Pine Tar Cough Syrup. He also sold products developed by his brother-in-law, Dr. Joshua Vick. Vick’s VapoRub and Vick’s Cough Drops are products still on today’s market. The Crystal Theatre plays silent flicks from the earliest days of moving pictures, including one by Thomas Edison. At the Hotel Clegg, you can sit down at the hotel’s switchboard and “eavesdrop” on the conversations of guests. Miss Porter’s one-room schoolhouse stands opposite the theatre and next door to the fire house, where Greensboro’s first steam engine is on display. Called the General Greene, the engine was built in 1888 by the LaFrance Fire Engine Company. It weighs 4,000 lbs., pumps 375 gallons of water, and was pulled by two horses. Also exhibited is the John and Isabella Murphy collection of Confederate firearms, a nationally-recognized collection which includes weapons from every Confederate armory, including six NC foundries. Outside the Museum, visitors can tour the late 18th century homes of Francis McNairy and Christian Isley. The Museum is at the intersection of Summit and Lindsay near the heart of downtown Greensboro. Hours are 10-5 Tuesday-Saturday and 2-5 Sunday. Admission is free. 336-373-2043

Greensboro

Guilford Courthouse National Military Park gives visitors the opportunity to walk the fields where American and British soldiers fought one of the most decisive battles of the Revolutionary War. Weathered cannon, bronze and granite monuments, battlefield tours, ranger talks, and museum exhibits present the story of the battle that all but ended British efforts to regain control of the Southern colonies. Although troops commanded by Lord Cornwallis held the field at the end of the bloody engagement, Guilford Courthouse was indeed a Pyrrhic victory for the British. Cornwallis lost more than a fourth of his fighting force during the two-hour encounter, causing him to retreat from his “victory” to the relative safety of Wilmington. His American adversary, Nathanael Greene, was meanwhile left free to move into South Carolina and gradually wrest back territory the British had gained the year before. In later years, the city of Greensboro was named in honor of the general whose “defeat” at Guilford Courthouse actually meant “victory” in America’s quest for independence.

The battle of Guilford Courthouse was fought in the morning hours of March 15, 1781. In the months leading up to the fight, successes the British had initially experienced in South Carolina and Georgia in 1780 were offset by unexpected reversals. Backcountry militia dealt a deadly blow to a regiment of British Loyalists at Kings Mountain in October, 1780. The following January, the feared Banastre Tarleton and his green-jacketed dragoons were humiliated by American militia and regulars under Daniel Morgan at Cowpens. Nathanael Greene then led Cornwallis on an exhaustive chase from South Carolina to Virginia, the so-called “race to the Dan” River, drawing British troops further and further from their supply bases while all the while seeing his own army more than double in number. When Greene finally opted to stand and fight, over 4,400 regulars and militia opposed some 2,000 British troops. Nicknamed “The Fighting Quaker,” Greene employed tactics similar to those used so successfully by Morgan at Cowpens. North Carolina militia formed his first line, Virginia sharpshooters formed the second, and veteran Maryland and Virginia regulars the third. When the British attacked, Greene’s first line fired two volleys, then broke and ran. The second line offered more resistance before also yielding. The British lines reformed and promptly engaged Greene’s final line, and soon the two armies were thoroughly enmeshed. When Patriot cavalry under Colonel William Washington threatened to give the advantage to the Americans, Cornwallis ordered his artillery to fire into the fray, killing friend and foe alike. Many British soldiers were felled by the “friendly fire,” but the tactic also forced the Americans to retreat, ending the battle.

Among the park’s many monuments is one honoring patriot officer Joseph Winston, for whom the city of Winston is named, and another dedicated to the three North Carolina signers of the Declaration of Independence – William Hooper, Joseph Hewes, and John Penn. Portraits of these individuals, and Nathanael Greene, for whom the city of Greensboro is named, are displayed in the visitor center.

The National Park is about six miles northwest of downtown Greensboro, off Battleground Avenue. It is open year-round from dawn to dusk and admission is free. Visitor Center hours are 8:30-5 daily except New Year’s, Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve, and Christmas Day. Special events, including encampments and tactical demonstrations, are scheduled the weekend nearest the anniversary of this critical battle of the War of Independence. 336-288-1776

High Point

An exhibit building and three historic structures give visitors to the High Point Museum & Historical Park a wealth of information about this Triad town. The spacious first-floor exhibit galleries focus upon many of the “high points” of High Point history. Largely settled by Quakers, the region experienced significant growth when the North Carolina Railroad was completed. Connecting Goldsboro with Charlotte, the railroad took a 223-mile, crescent-shaped route through the Piedmont, linking Raleigh, Hillsborough, Greensboro, Lexington, and Salisbury with its eastern and western terminals. According to legend, J. L. Gregg was responsible for giving High Point its name while surveying the shortest route for the NCRR. In charge of the railroad’s engineering party, Gregg determined that the place where the railroad route intersected the Fayetteville and Western Plank Road was 943 feet above sea level. He told his crew, “Men, this is the highest point along the whole survey; so we will mark it High Point.”

Exhibits spotlight some of the industries for which the High Point area has become famous, including examples of furniture that eventually earned the region its reputation as the “Furniture Capitol of the World.” The Perley A. Thomas Car Works, which moved to High Point in 1910, originally built streetcars; today the company manufactures perhaps the most recognizable vehicle on America’s highways – the yellow school bus. Other exhibits display changes in technology, social customs, and popular culture, and a small exhibit on musician John Coltrane, one of the famed “Carolina Be-Bop Kings.” A new featured attraction is “Meredith’s Miniatures,” a collection of 30 highly-detailed miniature rooms by High Point native Meredith Slane Michener.

The historical park also includes High Point’s oldest surviving structure, the John and Phebe Haley House, completed in 1786. Facing the new Salisbury Road which connected Guilford Courthouse with the Rowan county seat, its location naturally led to the brick house becoming a popular stopping point for teamsters. Although the Haleys never used their home as a tavern, subsequent owners did. When Jonathan Welch acquired the property in 1838, he hung out a sign reading “J. Welch, Entertainment” and soon earned a reputation for providing wayfarers with good food and drink, pleasant company, and comfortable lodging. This building served as a residence well into the 20th century. Like the Haley house, another home built to last was the log cabin raised by Philip and Mary Hoggart around 1801. Beginning as a simple one-room cabin, a second room was added later. The chestnut timber used in its construction provided good insulation, keeping the house cool in the summer and warm in the winter. The wood’s natural resistance to moisture and insect damage also helped keep the house structurally sound for more than 200 years, and the home remained in use until the 1960s. Along with these two homes, the park also includes an 18th century blacksmith shop. Museum hours are 10:00-4:30 Wednesday through Saturday. Closed Sunday through Tuesday. Admission is free; donations welcomed. A gift shop is on the premises. The historic buildings are open 10-4 on Saturday only.

Greensboro

Certain ordinary, everyday occurrences are more extraordinary than others. Take, for example, four college classmates who stop off at a downtown lunch counter for a bite to eat. One wonders what they might have ordered, had they been given the opportunity – a burger and fries, perhaps, or a cup of coffee and a slice of cherry pie. Maybe they had no idea of what to ask for, because they already knew when they sat down that they wouldn’t be served. And that was the whole point. In February, 1960, the lunch counter at Woolworth’s in Greensboro was for “whites only,” and the four students, freshmen attending the Agricultural and Technical College of North Carolina, were men of color. So began one of the defining moments of the mid-20th century’s civil rights movement. This historic sit-in, along with many other events across the nation pertaining to the battle for equal rights, is appropriately spotlighted in that very same Woolworth’s store, now the home of the International Civil Rights Center & Museum.

For several months in 1960, from late winter to early summer, the eyes of America were on Greensboro. The peaceful sit-in movement at the lunch counter started on February 1 by Franklin E. McCain, Joseph A. McNeil, Ezell A. Blair, Jr. [now Jibreel Khazan], and David L. Richmond gained national attention. As the sit-ins continued over the next weeks and months, store manager Clarence Harris realized that the protest was costing money, less at the lunch counter than in overall sales decline due to lost traffic. Harris quietly arranged for several of Woolworth’s black employees to change into their street clothes and sit down at the counter as regular patrons. On Sunday, July 25, 1960, without incident or fanfare, the “whites only” lunch counter was no longer segregated.

Four decades later, the vacant Woolworth building was nearly razed to make way for a parking lot. Two local officials, Earl F. Jones and Melvin “Skip” Alston [current chairman of the ICRCM] had another idea for the property. They had hopes of turning the site of the crucial civil rights victory into a museum. Their dream became reality on February 1, 2010, the fiftieth anniversary of the first sit-in, when the International Civil Rights Center & Museum opened its doors.

The 43,000 square foot facility lets visitors revisit some of the most important events in the human rights struggle of the 1950s and 1960s, including, of course, the famous lunch counter. While standing at the counter and hearing about the events surrounding the sit-in, visitors might want to check out the prices of some of the menu items – a glass of Pepsi cost a nickel, a slice of apple or cherry pie cost 15 cents, and a turkey club sandwich sold for 65 cents! Other exhibits spotlight the 1954 Brown vs. Topeka Board of Education Supreme Court ruling that signaled the beginning of the end of “separate-but-equal” school systems; the 1957 demonstrations in Little Rock, AK, protesting desegregation; and the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham [nicknamed “Bombingham”], AL in which four girls were killed. According to Bamidele Demerson, the Center’s executive director, one of the Museum’s most prized artifacts is also one of its smallest – a pen used by President Lyndon B. Johnson to sign the historic 1965 Voting Rights Act. Mundane items are sobering reminders of blatant discrimination – separate entrances and waiting areas for blacks at train stations and bus depots; segregated seating in the balcony [the “buzzard’s roost”] at movie theaters; restroom doors and water fountains marked “whites” and “colored.” The Center is at 301 North Elm, mere blocks from the heart of downtown Greensboro. Summer hours (April-September) are 9-6 Tuesday-Thursday, 9-7 Friday and Saturday, and 1-6 Sunday. Admission charge. Guided tours are conducted hourly. 336-274-9199

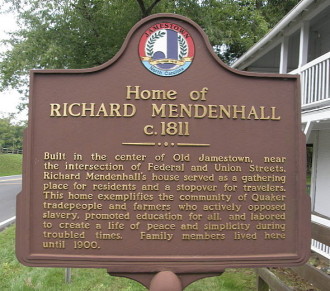

Jamestown

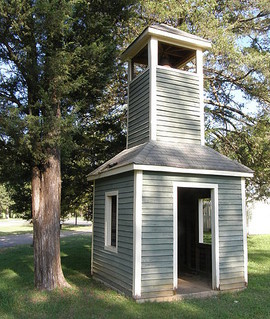

The Richard and Mary Mendenhall Plantation is a sprawling affair built in two distinct phases over a 30-year interval. The original house, built circa 1811, was constructed of brick. The two-story structure utilized a typical hall-and-parlor floor plan downstairs with two bedrooms above. The Mendenhalls entertained neighbors and wayfarers and had seven children of their own, so an addition in the 1840s was more than justified.

The house nearly doubled in size with the addition of a new parlor, hallway, stairway, and bedroom. During this renovation, the space between the main house and the separate kitchen was enclosed, creating a gathering room downstairs and a garret room upstairs. It also meant that the first floor contained four distinct levels. A wrap-around porch added to the front, side, and rear of the house completed the renovations. Guests today will enjoy navigating the narrow, winding steps that lead from the original parlor to the master bedroom above. They will also be intrigued by the half door cut into the rear wall of the master bedroom, a feature that enabled furniture too large for the stairway to be hoisted up from outside.

The Mendenhalls were Quakers, and their house reflects a humble lifestyle. Mantels are plain and unadorned, and furnishings are simple and functional. Visitors might be surprised to see how ladder-back chairs could be hung from pegs placed high on the walls to make way for living space. One of the interesting items displayed in the “new” parlor is a framed copy of the family’s original land purchase. On May 10, 1744, the Earl of Granville sold a sizeable tract of land for 10 shillings sterling to Richard’s grandfather, James Mendenhall, for whom Jamestown was named. At the time of purchase, the land was a part of Rowan County.

The plantation features several original dependencies, including the two-story springhouse. The construction of this building enabled half of the ground floor to be used as a springhouse and half to be used as a smoke-house, while the second floor served as a pantry. The farm’s “Pennsylvania bank barn” stands nearby. This design was rarely seen in North Carolina, but the style is similar to that used for barns in Pennsylvania, where Richard trained as an apprentice in his youth. The barn is built on the slope of the hill in such a way that both floors can be reached from ground level. Today the barn features a collection of horse-drawn vehicles, including a false-bottomed wagon used during the time of the Underground Railroad. Quakers vigorously opposed slavery, and the Mendenhalls helped many blacks escape to the North. It is speculated by some that runaway slaves were occasionally harbored in the Mendenhall’s basement. Another building on the property is the Lindsay House, moved from its original location in 1983. This 19th-century two-story frame house was an early medical school. The Historic Jamestown Society, Inc. operates Mendenhall Plantation. Hours are 11:00-3:00 Friday, 1:00-4:00 Saturday, and 2:00-4:00 Sunday. Admission charged. Tours are self-guided. Handouts for the main house and outbuildings provide details about the rooms and furnishings. 336-454-3819

Greensboro

The Natural Science Center of Greensboro offers so much to see and do that visitors can easily spend a full morning or afternoon among the varied exhibits. The outdoor Zoological Park is home to dozens of animals from around the world, while dozens more mounted animals are showcased inside. The center features a small aquarium, herpetarium, hands-on herpetology lab, and dinosaur gallery. There’s a weather exhibit, a human body gallery, an impressive gem and mineral collection, and, as further proof that the center is a “swinging” place to visit, the lobby features a Foucault pendulum with a 61-pound bob held by a 220-foot wire. The pendulum helps to demonstrate the Earth’s rotation. All these exhibits are included in one low admission charge; for a small additional fee, visitors can enjoy one of several films shown in the “total immersion” OmniSphere Theater.

With so many diverse activities available, it might be hard to choose where to start. The Animal Discovery section is populated by such assorted critters as anteaters and otters, meerkats and monkeys, crocodiles and cockatoos. Tigers are on hand as well, along with lemurs, wallabies, and giant tortoises. The Friendly Farm is home to goats, sheep, pigs, miniature burros and horses, and alpacas. Keeper talks are given daily at 11:30, 1:30, 2, and 3:30. Among the mounted species displayed indoors are an African lion, a spotted hyena, and a Kodiak bear.

The Dinosaur Gallery features a fearsome, life-sized representation of a Tyrannosaurus, along with skeletons of a triceratops and a stegosaurus. Dinosaur tracks are seen here as well, along with fossilized plants, animals, amphibians, and fish, and several examples of petrified wood. The aquarium and herpetarium are located downstairs. Among the reptiles exhibited in the latter are rattlesnakes, pythons, anacondas, and Gila monsters. In the herpetology lab, visitors can touch a variety of non-poisonous snakes and lizards. Sharp-eyed visitors will see a live, two-headed, yellow-belly slider turtle, found in Badin Lake, NC in 1999.

The Center’s health quest gallery has a way of getting under your skin in a literal sense, using preserved human bodies and body parts to educate visitors about the heart, lungs, and other organs. The Extreme Weather exhibit focuses on tornadoes, floods, hurricanes, and blizzards.Hours are 10-4 seven days a week. Admission charged. Films shown in the OmniSphere Theater incur an additional charge. 336-288-3769

Greensboro

Tannenbaum Historic Park, adjacent to the Guilford Courthouse National Military Park, gives visitors the opportunity to learn about 18th century farm life. The park centers on the restored farmstead of Joseph Hoskins. During the hours leading up to the historic battle, the farm served as a staging area for British troops. In addition to the house, kitchen, and barn, the site also includes the Colonial Heritage Center, with exhibits depicting life before, during, and after the battle and original paintings by noted military artist Dale Galleon. A museum store and picnic grounds are also located at the Park. Tannenbaum is about six miles northwest of downtown Greensboro, off Battleground Avenue. It is open Tuesday-Sunday. Admission is free. 336-545-5315

Guilford County is bordered by ALAMANCE, DAVIDSON, FORSYTH, RANDOLPH, and ROCKINGHAM counties.

Return to REGION SIX HOME PAGE.

Return to GEOGRAPHIC REGIONS HOME PAGE.