PENDER COUNTY

Scroll down this page or click on specific site name to view features on the following Pender County attractions/points of interest:

Missiles and More Museum, Moores Creek National Battlefield, Pender County Museum, Penderlea Homestead Museum, Poplar Grove Plantation

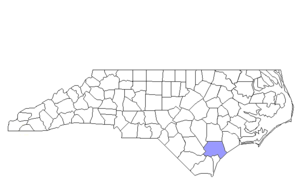

Fast facts about Pender County:

Created in 1875, the county is named for Confederate General William Dorsey Pender, mortally wounded at the Battle of Gettysburg.

The county seat is Burgaw. Other communities include Hampstead, Penderlea, Topsail Beach, Scotts Hill, and Surf City.

Pender County’s land area is 870.67 square miles; the population in the 2010 census was 52,517.

It is worth noting that Sloop Point Plantation, a private residence near Hampstead, is believed to be the oldest house in North Carolina, dating to 1726 or earlier.

Below: The Pender County Courthouse

Topsail Beach

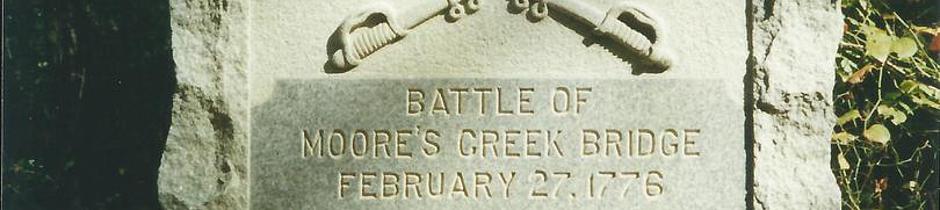

The Missiles and More Museum is housed in an original, blast-proof missile assembly building and provides displays, photographs, launch videos, and other information pertaining to “Operation Bumblebee,” a little-known chapter in our nation's race for space. Back in the first quarter of the 18th century, it’s possible that pirates like Blackbeard and Stede Bonnet buried their treasure on Topsail Island. Stories of buried treasure may be fiction, but it is an unquestionable fact that, for a couple of years following World War II, the United States Navy dug in. In conjunction with the Johns Hopkins University physics lab, the Navy started “Operation Bumblebee,” which was the true beginning of the US space program. Roads, a bridge, a fresh water supply, and other improvements were made on the island as the military directed operations from nearby Camp Davis in Holly Ridge on the mainland. Between 1946 and 1948, more than 200 rocket launches were made; these tests proved the feasibility of ramjet engines that could propel aircraft beyond the speed of sound.

Among the Museum's collection of artifacts is a full-size Talos guided missile, displayed near the entrance to the repurposed assembly building; inside is a booster rocket, nicknamed a "flying stovepipe," that was recently discovered off shore. Eight four-story concrete observation towers were originally built along Topsail Beach to monitor and film rocket launches. Not part of the Museum, seven still remain along the beach. All but one have been repurposed; tower # 2, empty and open for inspection, has been added to the National Register of Historic Places. Subjects covered under the heading of “More” include Camp Davis; the Women Air-force Service Pilots (WASPs) who served at Camp Davis; pirate lore; and Topsail Island itself. 910-328-8663

Currie

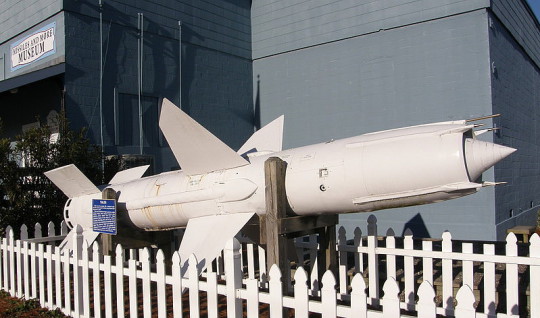

Visitors to Moores Creek National Battlefield, located in rural Pender County 20 southwest of Burgaw, will discover that the brief skirmish which took place here in the early morning hours of February 27, 1776, had an instrumental part in determining what role North Carolina would play in the War of Independence. The patriot victory significantly altered British plans for maintaining military control in the southern colonies. Moreover, it emboldened members of North Carolina’s 4th Provincial Congress convening in Halifax in April, 1776, to authorize the colony’s delegates attending the Second Continental Congress to vote for independency.

In February, 1776, a force of some 1,600 men gathered at Cross Creek (present-day Fayetteville) to begin a march to Wilmington. These men were Scottish Highlanders who had migrated from the north of Scotland to the North Carolina colony beginning in the 1760s and had settled in the southern piedmont region of the province. For the most part, these Highland Scots bore little love for the British; in fact, many of them had actually taken up arms against the English years before. Led by Bonnie Prince Charles, the Highlanders made a bid for Scottish independence, only to be soundly beaten in the Battle of Culloden in 1744. In the aftermath of that defeat, the Highlanders were allowed to return to their homes only after swearing an oath of allegiance to the British Crown, and agreeing to take up arms in defense of the King should they ever be called upon to do so. Many years later and thousands of miles removed from their original homeland, these Highlanders still felt honor-bound to abide by their oath, and so they gathered at Cross Creek in preparation for their march to Wilmington. There they were expected to join with an army of British regulars already under sail from New York City. Royal Governor Josiah Martin was convinced that the combined forces would provide a military presence of sufficient strength to dissuade Carolinians from participating in a seemingly imminent fight for independence. Once alerted to this plans, however, patriots under the command of Colonels James Moore, Alexander Lillington, and Richard Caswell took steps to intercept the Loyalists at some point north of Wilmington. The Loyalist Highlanders successfully skirted the patriots’ initial attempts to block them, but eventually the Whigs were able to position themselves at Widow Moore’s bridge, a crucial crossing along the stage road.

A small number of militiamen were used as decoys. An envoy to their camp ob-served that the Whigs were few in number and encamped with the creek to their back, cutting off their avenue of escape. This information was relayed to General Donald MacDonald, who, though reluctant to commit his troops to battle, acquiesced to his junior officers’ call for action. Major Donald McLeod was placed in command of the attacking forces. After marching through dark, swampy wetlands, the Highlanders arrived at the patriot campsite only to find it deserted. When a few shadowy figures were seen on the opposite site of the creek, McLeod assumed they were stragglers. He ordered his men to cross what was left of the bridge, the patriots having removed the planks and greased the bearers to make a crossing as difficult as possible. Once the main body of Highlanders was on the south side of the creek, McLeod ordered an assault on what he presumed to be a token force. Instead, he ran headlong into a well-entrenched force of nearly 1,000 minutemen and militia.

Concentrated fire from muskets and rifles, a three-pound cannon affectionately nick-named “Mother Covington” by the patriots, and a half-pound swivel navel cannon (“Mother Covington’s daughter”) made quick work of the Highlanders. The skirmish lasted less than three minutes. 30 Scots were killed, 40 wounded, and hundreds taken prisoner. Private John Grady was the sole Patriot casualty. Highlighting the battleground tour are several memorials, including the Patriot (Grady) Monument, the Loyalist Monument, honoring the heroic Highlanders who “did their duty as they saw it,” and the Women’s Monument. Reconstructed earthworks outline the position taken by the patriots, and a replica bridge spans the creek. The Visitor Center features electric maps, artifacts (including a British long rifle and a Scottish officer’s pistol), and a ten minute film. Hours are 9-5 daily except Christmas and New Year’s Day. Admission is free. The one-mile history trail is self-guided. Groups may arrange guided tours by contacting the park staff in advance. Living history weekends are held periodically during the year. The major annual event is the Battle Anniversary Weekend held the last weekend in February. 910-283-5591

Burgaw

Appropriately located in the county seat of Burgaw, the Pender County Museum takes its job of preserving local history seriously. Since its opening in 1980, the Museum has showcased an eclectic mix of artifacts and antiques that call to mind days gone by. Items in the collection include household furnishings, period fashions, early medical equipment, old farming equipment, and other miscellany. The Museum is particularly proud of its collection of interviews with 41 area veterans of World War II, along with artifacts from that great conflict. The house used as the county museum is interesting in itself. Built in 1917, it is the oldest brick house in Burgaw and was originally the home of Amos Burton, at one time the mayor of the town. Hours are 1-4 Thursday and Friday and 10-2 Saturday. Admission is free. 910-259-8543

Willard

The Penderlea Homestead Museum is something quite different from the norm – it preserves a part of a homestead community which had its beginnings during one of the worst periods in American history. Penderlea was the first of 152 farm settlement projects initiated in 1934, at the height of the Great Depression, as part of President Roosevelt’s New Deal. The aim was to provide bankrupt farm owners, unemployed farm hands, and destitute tenant farmers with the means to survive in self-sufficient rural communities. In the case of the Pender County settlement, 142 20-acre homesteads were created. Each included a modest home with 4-to-6 rooms, running water, and electricity. The homestead also included such dependencies as a barn, poultry house, hog house, corn crib, and combination wash house/smoke house. The hub of the community included a general store, social building, school, grist and feed mills, and assorted storage buildings.

Penderlea Homestead Museum is located in the former home of Grey and Sue Murphy, two of the original homesteaders. Their 2-bedroom home was one of the first ten houses built on Penderlea; only one-third of the 300 homes built on Penderlea survive. The site is open from 1-4 Saturdays only. Admission is free. 910-285-3490

Northeast of Wilmington

Poplar Grove Plantation stands nine miles north of Wilmington, just inside the Pender County line. Since 1980, this site has been interpreting the 19th century lifestyles of coastal North Carolina. Poplar Grove Plantation was home to six generations of the Foy family before being purchased by the non-profit Historic Poplar Grove Foundation in 1971. James Foy, Jr. purchased a 628-acre tract in 1795 and built the first family home. This original structure stood in a grove of poplar trees, giving the plantation its name. The Greek Revival-style manor house which graces the site today was built in 1850 by his oldest son, Joseph Mumford Foy, to replace the earlier home, which had burned down. The later house is a two-story, weatherboard frame house above a raised basement. Each floor has two rooms to the left and right of a central “shotgun” hallway. Handsome interior appointments show affluence, but are far from ostentatious. Wallpaper is used in some rooms, for example, but not all. Mantels – the house has twelve fireplaces – are simple and unadorned. Pine flooring was covered by oak in the early 20th century, except in the dining room, for a very practical purpose – food spills might have stained oak flooring, but pine flooring resisted such staining. The heart pine used in the construction of the house was cut at the plantation’s sawmill, and the bricks used for the raised foundation were made on site as well.

Guided tours take visitors through most of the house, including the front and back parlors, morning room, and dining room on the first floor; four bedrooms on the second floor; and one room in the basement that serves as an exhibit area. The visitors desk and gift shop occupy another portion of the basement. Included among the household artifacts is a deed box, family Bible, and a claim for reparations for livestock and feed taken by the U. S. Army during the spring of 1865 as the Civil War drew to a close. Another item of note is the one-shot derringer owned by Mrs. Nora Foy. In the 1870s, after the railroad line was completed, the federal government established a post office for the Scotts Hills community, and Mrs. Foy was named postmistress, the first woman in the country to be given this job.

The smokehouse and kitchen are two dependencies which can be visited following the tour. Though no longer operational, a windmill still stands at the back of the house. Erected in 1919, the windmill pumped water from the cistern to a holding tank; gravity carried the water into the manor house. Not far behind the main house is a tenant house, the only one remaining from the many which were located on the plantation. At the outset of the Civil War, there were 64 slaves at Poplar Grove; after receiving their freedom in 1865, all but one of them chose to remain on the property, becoming tenant farmers. The surviving house dates to 1930. Also on the premises are a basket-making studio, a weaving studio, a blacksmith shop, and an agricultural exhibit building. The latter displays a variety of farm implements, including a 1939 Livermon peanut picker. After the Civil War, Poplar Grove enjoyed success as one of the first peanut farms in the state. Also showcased is the carriage of Angus McLean, N. C. Governor from 1925-1929. Artisans are often on hand at the blacksmith shop, weavers’ studio, or basket studio to depict the traditional skills associated with these crafts.

From Wilmington, take US 17 By-Pass North. The plantation is immediately off the highway to the right after crossing into Pender County. Hours are 9-5 Monday-Saturday and 12-5 Sunday. Admission charged. Poplar Grove is closed Easter Sunday, Thanksgiving Day, the week of Christmas, and the entire month of January. Special events include the Classy Chassis Car Show in July, the Halloween Festival in October, and the Christmas Open House in December. 910-686-9518

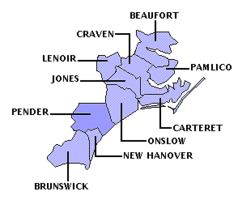

Pender County is bordered by BLADEN (Region Five), BRUNSWICK, COLUMBUS (Region Five), DUPLIN (Region Five), NEW HANOVER, ONSLOW, and SAMPSON (Region Five) counties.

Return to REGION THREE HOME PAGE.

Return to GEOGRAPHIC REGIONS HOME PAGE.