McDOWELL COUNTY

Scroll down this page or click on specific site name to view features on the following McDowell County attractions/points of interest:

Andrew's Geyser, Carson House, Linville Caverns, Mountain Gateway Museum, Old Fort Railroad Depot Museum

Fast facts about McDowell County:

Created in 1842, the county is named for Revolutionary War General Joseph McDowell, an officer at the Battle of Kings Mountain.

The county seat is Marion, named for Revolutionary War General Francis Marion, nicknamed “The Swamp Fox.” Other communities include Ashford, Dysartville, Glenwood, Little Switzerland, Nebo, Old Fort, Pleasant Gardens, Sugar Hill, and Woodlawn.

McDowell County’s land area is 441.68 square miles; the population in the 2010 census was 44,996.

West of Old Fort

When visiting Old Fort, you might want to pack a picnic basket or grab something to go at one of the area restaurants and head out to Andrew’s Geyser. Heading west on U. S. 70, turn right onto Old Highway 70. Drive 2.4 miles, then turn right onto Mill Creek Road. In two miles you’ll come upon Andrew’s Geyser on the left. The geyser was constructed in 1885 as a tribute to Colonel Alexander B. Andrews, a principal figure in the development of the Western North Carolina Railroad. Restored by the town in the 1970s, the nicely-landscaped open field is surrounded by woods and centers on the geyser, which shoots a stream of water some 70 feet up. Lots of shaded picnic tables are available.

West of Marion

Guests of the historic Carson House, located between Marion and Old Fort, get to visit the “birthplace” of a county. In the dining room of what was once a simple log home, citizens gathered in 1843 to help bring McDowell County into being. The home subsequently served as the seat of county government until a courthouse was built in Marion, on land donated by the Carson family. Scots-Irish immigrant John Carson built a single-room log cabin along the banks of Buck Creek about 1793. To this, a second log building nearly identical to the first was added later, connected to the original by an open breezeway, or “dogtrot.” The homestead was greatly expanded during the 1840s, at which time the structure assumed the current Greek Revival architectural style seen today.

The Carson family was active both politically and socially. John Carson earned the rank of colonel in the local militia during the Revolutionary War; was a delegate to the Fayetteville Convention in 1789, voting in favor of ratifying the United States Constitution; and served in the North Carolina House of Commons. His son, Samuel Price Carson, also lived a life of public service, serving three terms as state senator and four terms in the US House of Representatives. A heated congressional campaign in 1827, however, led to a duel between Carson and his opponent, Dr. Robert Vance. Vance was mortally wounded on the field of honor, and Carson was soon persuaded by friends Davey Crockett and Sam Houston to move to Texas. Here, Carson continued his life of public service, signing the Texas declaration of independence and serving as the new Republic’s first Secretary of State.

Younger son Jonathan Logan Carson thus in-herited the plantation and was responsible for its vast expansion and improve-ments. The log walls of the original buildings were cov-ered over with clapboard, interior walls were finished, and such fine accents as handsome carved mantles and fluted door and win-dow facings were added. First and second floor front porches were also added. After the home’s expansion, it served as a stagecoach inn and a gathering spot for the locals. Andrew Jackson was numbered among the inn’s many guests, and he reportedly gambled on horses that raced at the Carson plantation.

Guided tours run approximately 45 minutes and include the dining room, front parlor, and first floor bedroom. Second floor rooms include the master bedchamber and the daughters’ room and family sitting room. This floor also features an African-American Exhibit Room and a room displaying items associated with the spinning and weaving of flax, cotton, and wool. On the third floor are the Boarders’ Room, which accommodated stagecoach passengers and other guests, and the McDowell Room, which displays various and sundry articles related to McDowell County history. Artifacts about the house include family portraits, personal family items, and many original furnishings. A barn at the rear of the property includes a collection of hand tools and field plows, a mid-19th century covered wagon manufactured in Salem, NC, a delivery wagon, and several buggies. The house is open for tours April through November. Hours are 10-4 Wednesday through Saturday and 2-5 Sunday. Admission charged. 828-724-4948.

Linville Falls

Perhaps there's something in our DNA that draws us to waterfalls and caves. Although picturesque cascades can be found in many places in the western mountains of North Carolina, caverns are a different story. While there are actually more than 1,000 limestone caves scattered through the hills of North Carolina, there is only one cavern in the state open for tours. Tucked away under the gentle slopes of Humpback Mountain in McDowell County is Linville Caverns. Although lacking the scope and color of some of the better known show caves found in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, Linville Caverns nevertheless provides an interesting look inside a mountain.

The caverns were discovered as early as 1822, when local residents noticed fish swimming out of the base of the mountain. During the Civil War, deserters made practical use of the caverns, hiding from patrols in the dark recesses of the cave. In July, 1939, the caverns were opened commercially for the first time, under the ownership of John Gilkey. Gilkey went bankrupt the following year, however, when severe flooding shut down his operation. E. S. Collins bought the property at that time, spending a full year to clean out the cave and build retaining walls to help prevent later flooding. Nearly 70 years later, Linville Caverns are still owned and operated by the Collins family.

Tours run continuously during the day, so visitors rarely have to wait more than a few minutes before entering the cool, damp environs of the cave. Temperature in the cavern is 52 degrees year-round. Since the cavern “rooms” are relatively small, tour groups are usually limited to 10-12 people. A concrete floor installed in 1981 makes it easy for visitors to explore the cave, and the route is mostly level, with only a few steps needing to be climbed in order to enter an upper level. The walk runs about 600 feet into the base of the mountain and visitors will see an assortment of stalactites, stalagmites, and flowstone along the way. Some of the larger, more impressive formations have been given fanciful names such as “The Wedding Scene.” The largest and oldest formation, dating back 6 million years, is called “Frozen Niagara Falls.” The only gemstone found in the cavern is carnelian, also known as “cave onyx.” Visitors may spot a few cave critters as well. Trout still swim in the stream that runs parallel to the walkway, and, in winter, small bats will hibernate in the caverns.

Near the back of the cave is the “bottomless pool.” Divers have been unable to ascertain just how deep it goes, but the best guess is at least 300 feet. It’s near the upper room that tour guides will turn off the lights, plunging visitors into total darkness. It is usually at this point of the tours that visitors are told the true story of two 17-year-old valley boys who, in 1915, went to explore the cave without telling anyone where they had gone. When their one-and-only lantern fell into the stream, they were stranded in the dark. Fortunately, they had the stream to guide them, and, after two days of crawling on their hands and knees in the black void, they emerged, hungry but healthy. Folks familiar with the name of mineralogist William Earl Hidden might be interested know that , in 1884, he visited Linville Caverns at the request of Thomas Edison in search of platinum for use in Edison’s incandescent lamp. He carved his name in stone some 1,200 back from the cavern entrance. Linville Caverns open at 9 AM daily March-November and weekends only December-February. The caverns close at 4:30 PM out of season and at 6 PM June-August. Admission charged. 828-756-4171

Old Fort

The Mountain Gateway Museum in Old Fort provides numerous exhibits that help relate the history of the region and the quaint North Carolina town that began as a colonial outpost. The Museum is a complex of three buildings. The largest of these is a two-story stone building constructed by the WPA during the mid-1930s. Constructed on the site of the original colonial fort, this building was used as a community center until acquired by the McDowell County Historical Society in the 1970s. Visitors should start their tour by viewing a short video which gives a concise overview of the origin and growth of Old Fort. Cherokee Indians originally inhabited the region, but as hostilities erupted between the natives and white settlers along North Carolina’s backcountry at the outset of the Revolutionary War, the site gained strategic value. During his expedition against the Cherokee, Colonel Griffith Rutherford established a military post at the head of the Catawba River and left rangers behind to guard the stronghold after completing his mission. Years later, as settlers migrated in increasing numbers to the area, the village became known as Old Fort.

The town grew considerably when the railroad finally stretched into western North Carolina, and the elegant Round Knob Hotel just outside of town was a popular resort destination for the wealthy in the closing decades of the 1800s. The hotel burned in 1911. Museum exhibits cover a wide range of topics, including a collection of archival photos entitled “Mountain Life – from a bygone era.” One group of photos tells the story of Dr. Elisha Mitchell, famed UNC professor of mathematics, who lost his life while attempting to prove, using barometric measurement, that Black Mountain (renamed Mount Mitchell in his honor) was the highest peak in eastern United States. Another display on Southern Appalachian plant species details how local plants were used by Indians and early settlers for clothing and medicinal purposes. Catnip, for example, was used to treat coughs, wet tobacco leaves to soothe stings and bites, and milkweed to act as a purgative. Visitors who read closely will learn that kudzu was imported from the Orient and introduced to the region as a means of controlling erosion. Regrettably, no one gave any thought as to how to control the kudzu!

Mountain folk are known for their music, so it is appropriate that the museum features a collection of stringed instruments common to the area, including a banjo, mandolin, auto harp, and lap dulcimer, as well as a roller organ and a hand-cranked gramophone. There’s also a reconstructed one-room cabin built from logs from the first Presbyterian church in McDowell County, a display of 19th century farm implements, and even a moonshine still for the manufacture of corn whiskey.

Adjacent to the museum building are two cabins which have been moved to the site. The Morgan cabin, circa 1880, showcases a working loom, while the sparsely-furnished Stepp cabin, circa 1860, gives visitors a glimpse of the Spartan existence endured by early homesteaders. The town of Old Fort is just off Interstate 40 west of Marion. The Mountain Gateway Museum is open year-round, 9-5 Tuesday-Saturday and 1-5 Sunday-Monday. Admission is free, donations are accepted. 828-668-9259

Old Fort

At the very center of the business district is the Old Fort Railroad Depot Museum, sharing space with the visitor center inside the former train depot, built around 1892. The town grew considerably after the railroad arrived in the late 1860s, and the elegant Round Knob Hotel a few miles outside of town was a popular resort destination for the wealthy in the closing decades of the 19thcentury. Old Fort truly was the “gateway” to the North Carolina mountains and helper engines were stationed in town to assist westbound freight trains in making the steep grade up to Ridgecrest, and to help eastbound trains control their descent. Artifacts, memorabilia, and information related to the construction of the railroad from Old Fort to Ridgecrest to Swannoa Gap fill the old depot. Outside the building is the iconic symbol of the town, a 25-foot stone arrowhead carved from granite. Unveiled in 1930, the monument commemorates peace between pioneers and Native Americans. 828-668-7223

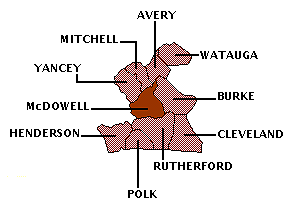

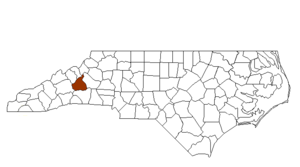

McDowell County is bordered by AVERY, BUNCOMBE (Region Ten), BURKE, MITCHELL, RUTHERFORD, and YANCEY counties.

Return to REGION NINE HOME PAGE.

Return to GEOGRAPHIC REGIONS HOME PAGE.